In two days of slaughter, a racist offensive including police and air bombers destroyed Tulsa, Oklahoma’s all-black Greenwood district. None of the perpetrators ever faced justice

By Matt Lebovic, The Times of Israel, 19-06-2020

During the course of Memorial Day weekend in 1921, a white mob eradicated the thriving black Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Between May 31 and June 1, some 300 of the neighborhood’s residents were killed, making the so-called “Black Wall Street Massacre” the most lethal racial “pogrom” in US history.

“Dubbed the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, this man-made calamity could more accurately be labeled an assault, a disaster, a massacre, a pogrom, a holocaust, or any number of other ghastly descriptors,” writes Tulsa attorney Hannibal Johnson, the author of “Black Wall Street”and education committee chair of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission.

Among the massacre’s pogrom-like elements, a blood libel-like charge of sexual assault was used to incite a white mob. Specifically, the son of a prominent black businessman was accused of assaulting a white girl who was an elevator operator. Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old shoe-shiner, was taken into custody and brought to the courthouse.

For generations, lynchings had been used by white supremacists to instill fear in blacks. Concerned about the fate of Rowland, a group of armed black men went to the courthouse. At the time, Tulsa was home to 3,200 Ku Klux Klan members.

A gunfight outside the courthouse left 12 people dead, and the black defenders fled back to the neighborhood. The mob was not far behind, intent on taking revenge.

In the racially segregated Tulsa, the Greenwood district was home to several black millionaires. Some of them raised capital to support the growth of “Black Wall Street,” while others had wealth from the oil boom. Only two generations removed from slavery, Greenwood was an “American Dream” for its 10,000 black residents — and a source of seething resentment for many whites.  The Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma (public domain)

The Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma (public domain)

Among the district’s amenities was the country’s largest black-owned hotel and a black hospital. There were two movie theaters, groceries, and a black newspaper.

The Tulsa Race Massacre did not occur in a vacuum. The “Red Summer” of 1919 saw so-called “race riots” in dozens of US cities. More often than not, local police joined white mobs in attacking black communities. In some cities, including Chicago, blacks put up an armed defense against white marauders.

However, the word “riot” does not capture what happened on the streets: Increasingly, historians are turning to the label massacre, or “pogrom,” to describe the destruction wrought upon the neighborhoods.

“The term riot is contentious, because it assumes that black people started the violence, as they were accused of doing by whites,” says Smithsonian Museum programmer John W. Franklin in a Smithsonian Magazine article. “We increasingly use the term massacre, or I use the European term, pogrom.”

Franklin’s grandfather, lawyer Buck Colbert Franklin, wrote a 10-page eyewitness account of the Tulsa pogrom that is now housed in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In Tulsa, the mob attacked blacks not only from the street, but also from the air. At the height of the pogrom, private airplanes were used to drop firebombs (“burning turpentine balls”) onto buildings, which proceeded to burn from the top down. Also from the planes, gunmen strafed black residents fleeing the district.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top,” wrote Franklin.

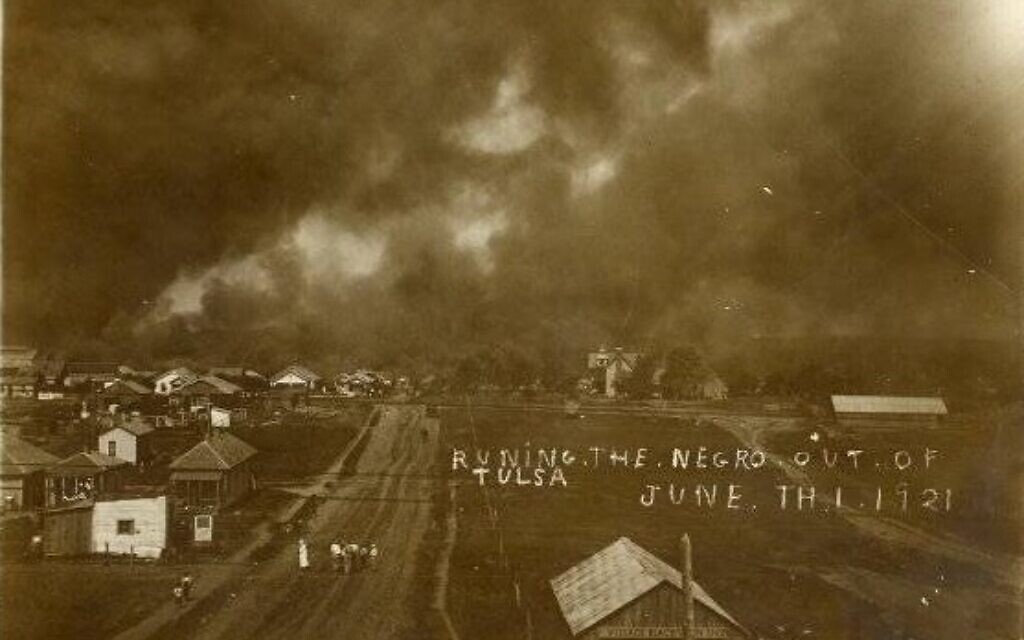

“The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top… I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?’” Franklin wrote. ‘Race riot’ postcard from the 1921 massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma (public domain)

‘Race riot’ postcard from the 1921 massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma (public domain)

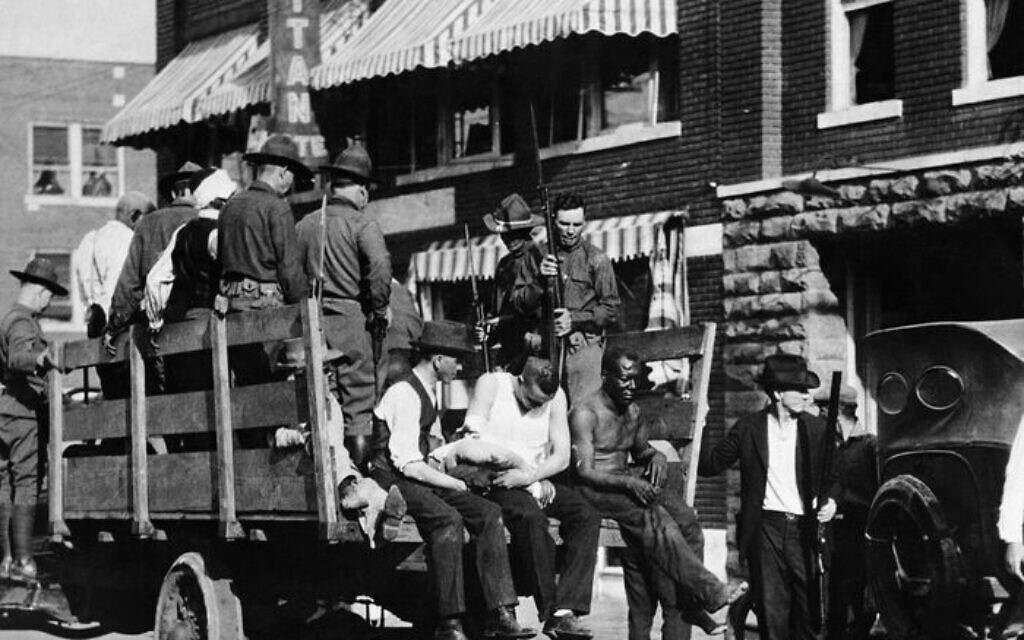

As punishment for the eradication of their neighborhood, 6,000 Greenwood residents were rounded up and detained by the National Guard. Some of them were held for more than a week, along with an additional 4,000 blacks from other parts of Tulsa.

‘Heavily armed resistance’

After the initial confrontation outside the courthouse, the burning and looting of Greenwood began.

Municipal officials were indeed complicit with the mob, ensuring that phone and rail services were shut off. The Red Cross was blocked from entering Tulsa, and firemen were prevented from entering the district at gunpoint. Civil officials deputized white men and handed out guns, encouraging people to restore order. Black man taken away during the Tulsa Massacre (public domain)

Black man taken away during the Tulsa Massacre (public domain)

By the early morning hours of June 1, gunfights had broken out between Greenwood’s black defenders and the white invaders. It was at this point that fires were started from both the ground and air while residents tried to flee.

“They were not used to meeting such heavily armed resistance,” said Chris Messer, an expert on the massacre and sociology professor at Colorado State University Pueblo.

“There was an understanding among whites locally that blacks got what was coming to them,” said Messer in an interview with The Times of Israel.

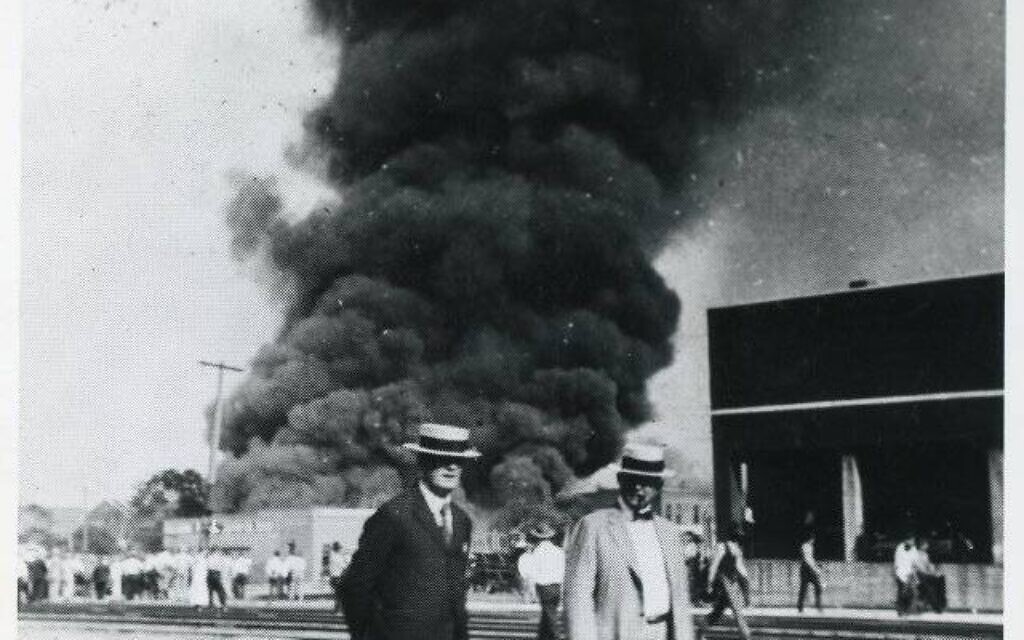

Although martial law was declared, in practice there was mob rule for two days. “Riot postcards” produced after the massacre included graphic images of carnage, including blacks being shot, decapitated, and set on fire. White men with the Greenwood district burning behind them, June 1, 1921 (public domain)

White men with the Greenwood district burning behind them, June 1, 1921 (public domain)

In addition to 300 black residents who lost their lives, some 800 people were treated for injuries and 35 neighborhood blocks destroyed. When National Guardsmen gave testimony about what took place, they referred to black residents as “the enemy.”

Although the massacre was reported in the national news, none of the perpetrators faced justice. The victims did not recover their property or receive compensation, and local authorities worked assiduously to ban memory of what took place for decades. More than 1,200 black homes had been burned to the ground.

In 1996, activists succeeded in bringing the massacre to the public’s attention. The Tulsa Race Massacre Commission was set up and made several recommendations, including reparations for survivors and the creation of a memorial park. Blacks rounded up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 1, 1921 (public domain)

Blacks rounded up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 1, 1921 (public domain)

In 2017, the Tulsa Fire Department put out a monograph for its 100th anniversary. Conspicuously, the massive inferno of 1921’s Memorial Day Weekend did not make the retrospective.

“The historical evidence had been suppressed,” said Messer. “Oklahoma history never taught about the massacre. But they do now.”

According to Messer, the massacre was covered locally “in such stark contrast to what actually happened.” Since the late 1990s, archeologists have been searching for mass graves related to that weekend of slaughter. Burnt out ruins of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 1921 (public domain)

Burnt out ruins of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 1921 (public domain)

Fifteen years ago, when Messer first encountered the Tulsa massacre in his research, the assault was commonly called a “race riot.” Eight decades after the massacre, there was more awareness of what took place in Greenwood, including the pogrom-like elements of the incident.

“Local officials contributed to the Tulsa Race Massacre,” said Messer. “They armed whites. They participated in the destruction themselves.”

In the years to come, other black neighborhoods and towns would be razed to the ground by white mobs. Two years after the events in Oklahoma, the black town of Rosewood, in central Florida, was similarly destroyed. As with the Tulsa Race Massacre, charges were never pressed and the memory of what took place was suppressed for decades.