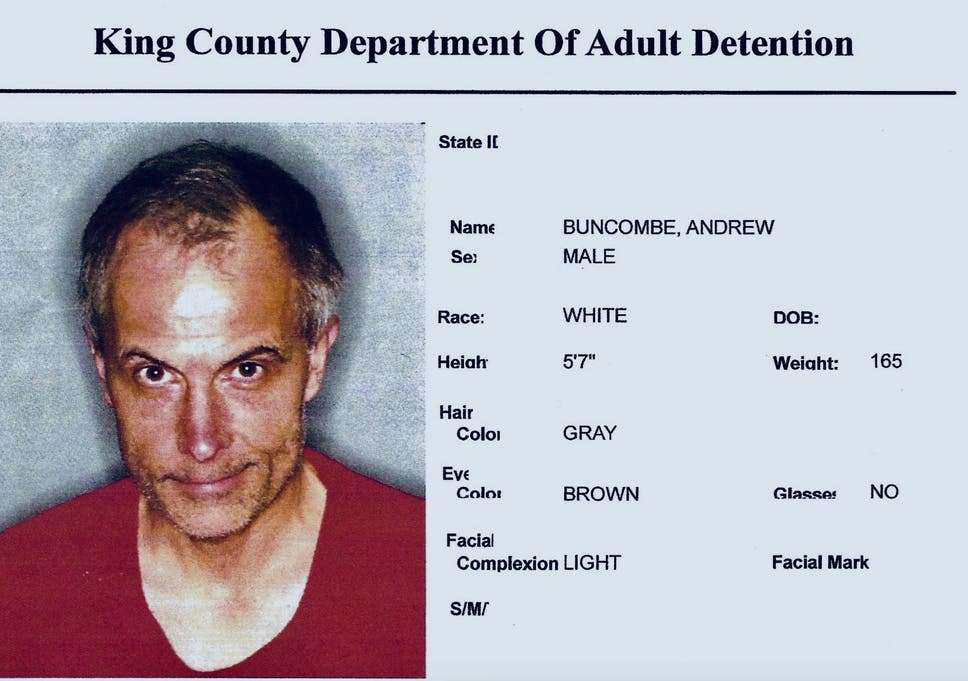

- In his 30-year career, The Independent’s Chief US Correspondent Andrew Buncombe has filed dispatches from across the world. Last week, while reporting on protests in Seattle, he was arrested for the first time. What he saw next throws the spotlight on a broken criminal justice system

The Independent employs reporters around the world to bring you truly independent journalism. To support us, please consider a contribution.

Seattle’s protest in support of Black Lives Matter was established just days after the killing of George Floyd. To the participants and their supporters, the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP) was a living experiment in how a community might exist without police. To their detractors, most vocally Donald Trump, who denounced them as anarchists and terrorists, the protesters and the six city blocks they had been ceded were proof of liberals gone mad. It was quirky and it was controversial.

For a month, as demonstrators marched in cities around the world, demanding racial justice and the defunding of police departments, Seattle’s protesters existed in an uneasy half-life, partly tolerated by a mayor keen to avoid more violence, and despised by those who thought the police had been wrong to abandon the area.

Then, on July 1, the city decided the experiment was over. It was time to clear the protesters.

How badly did Seattle need to retake those streets? Enough to arrest a journalist covering the operation?

Were the authorities so deaf to what protesters had been saying about police overreach and use of excessive force they were prepared to shackle that reporter, charge him with “failure to disperse” and then assault him?

Were they so oblivious to how jails across the nation had become hotspots for coronavirus they would put that person in a dirty, overcrowded cell where efforts to counter the disease were minimal?

Apparently so.

As police swept through Cal Anderson Park and the streets around it, officers with long sticks, backed up by armoured vehicles, were retaking the buildings of the East Precinct. They arrested dozens of people. I was among them.

“Enough is enough,” Seattle Police Department (SPD) chief Carmen Best said later that day. “Our job is to protect and to serve the community, our job is to support peaceful demonstrations, but what has happened here… is lawless and… brutal.”

City officials may have had good cause to retake the area “ceded” last month by mayor Jenny Durkan in an attempt to defuse protests triggered by the killing of George Floyd. While days in the zone had been overwhelmingly peaceful, at night there had been a number of criminal incidents, including six shootings, two of them fatal, with one of those deaths being of a 16-year-old. But the way the officers went about it, wielding sticks and mace, pressing people’s faces into the streets as they forced their hands into handcuffs, appeared heavy-handed at least.

Given how police from Washington DC to Minneapolis had dealt with protesters this spring, with tear gas, riot shields and rubber bullets, it may have been naive to think Seattle would be different. In comparison to the police in other cities, perhaps the SPD went easy.

It did not feel that way. Five minutes after having arrived the park, dispatched by my editors to cover the police operation and speak to protesters, I was arrested at its northern edge by an officer standing on a slight rise and behind black and yellow tape that read “Police line – Do not cross”. I was the other side of that tape. I did not cross it. At no point did I try to cross the police line.

The officer told me the park was out of bounds, and I needed to step back. I held up my State Department-issued press badge and told him I wanted to get some photographs of what was happening.

The officer again told me to retreat and said he was going to arrest me if I did not. I again told him I was a member of the media and intended to stay and do my work. He then grabbed me and marched me towards several of his colleagues, who pinned my hands behind my back.

All the officers were armed, one with an automatic rifle, a detail that may shock readers from nations whose police forces are not kitted out routinely with such a degree of weaponry, but not anyone in the US, where police departments are massively militarised.

The officers took my phone, and told me I was under arrest. I requested several times that they tell me what I was being charged with, and read me my rights. They told me I had the “right to remain silent”, but were unable or unwilling to tell me the charge.

They then handcuffed me, shackled my ankles and loaded me into a van. The police van set off to the West Precinct, stopping to collect arrested protesters. One man spent the journey shouting “Black Lives Matter”; a woman sobbed.

At the precinct, I again informed people I was a journalist, and asked to call my lawyer, my editor and the British embassy. I asked them to contact my local congresswoman. They took my photograph and told me I was being charged with “failure to disperse”, under a Washington state law that requires the accused to have been part of a group of four or more. I had been standing by myself. The maximum penalty is 364 days in jail and a fine of $5,000.

After an hour in a holding cell, the handcuffs still on, somebody again put leg irons around my ankles, and connected the two with a piece of chain pulled tight around my stomach. Were we heading to Guantanamo Bay? A woman also under arrest kept saying she did not speak English and requested a Navajo translator. “I think you speak English just fine,” mocked one officer.

In the van, the woman insisted on lying lengthways in the compartment she was in. I was squeezed into a tiny, claustrophobic section, perched on a narrow bench, trying not to slip off as the van sped through the city’s boarded-up downtown, towards the jail. By this point, the so-called “belly chain” had become so tight I could not fully exhale. It felt obscene and preposterous to have to inform the officers I could not properly breathe, that phrase having become weighted with such power and resonance during the Black Lives Matter movement, echoing the gut-wrenching final words of George Floyd. But that was the situation. I could not properly breathe.

One of the officers responded: “If you can speak, you can breathe.”

More prisoners than any other nation

The United States arrests and incarcerates more people than any other country.

The Brennan Centre’s Lauren-Brooke Eisen said while it accounts for 5 per cent of the world’s population, America is home to 25 per cent of those incarcerated, around 2.2 million. Around 95 per cent are in jail for non-violent offences.

There are more than 6,000 jails and prisons, at local, state and federal level, along with immigration detention facilities. People of colour are vastly over-represented, accounting for 32 per cent of the population but 56 per cent of prisoners. (My presence contributed to the white population of jails.)

Many say the system is broken. Others suggest the system may be in need of reform but that it does precisely what it was intended to do – namely to repress black and brown Americans, and the poor. Historians such as Carol Anderson, professor of African American studies at Emory University and author of White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, trace a direct line through the end of slavery to the establishment of the Jim Crow era and the current criminal justice system.

In her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander says today’s system, large parts of it privatised, overtly targets black men and decimates black communities. “In each generation, new tactics have been used for achieving the same goals – goals shared by the founding fathers,” she writes. “Denying African Americans citizenship was deemed essential to the formation of the original union. Hundreds of years later, America is still not an egalitarian democracy.”

Both the SPD and King County, which operates the Seattle jail where I found myself, have long been a part of that system. As recently as 2011, the Department of Justice accused the SPD of racial bias and use of excessive force. The appointment of Carmen Best, who is African American, as its chief in 2018 was part of an undertaking to reform.

King County, which has its own police force, has a similar record of disproportionate arrest and detention of black and indigenous people. One issue repeatedly pointed out by activists is the large number black and brown youths locked up. A report from 2016 showed half of youths in detention were black, whereas the black population of the county was 13 per cent.

‘Get back in the cell. You’ve lost your chance’

Seattle’s jail is located on 5th Avenue, a short distance from the waters of Elliott Bay. The area is known as the first place occupied by white settlers, in 1850, though for many centuries before it was home to indigenous Duwamish people.

By the time I arrived, the processing area was crowded with protesters rounded up that morning. I assumed that once jail officials had been informed I was a reporter, I’d simply be let go. At the West Precinct station I spotted several FBI officers who appeared to have been part of the operation. I yelled to them that I was a reporter. The First Amendment, guaranteeing the freedom of the press, is, after all, a federal issue, a constitutional right. I could not hear their entire response but they seemed to indicate the SPD were handling matters.

Momentarily, it appeared the situation was about to improve. The shackles and handcuffs were removed, but only so I could be ordered to remove all my clothes, and put on a blood-red prison “uniform” of trousers and jacket, and orange flip-flops. I protested this and protested too the demand I hand over my wedding ring. (One official said it could be stolen from me by another prisoner.)

In the end, I was permitted to keep the ring, but forced to wear the red outfit. Its impact was startling; immediately I felt out of place, disorientated and disempowered. It even started to make me feel guilty, as if I had done something wrong.

This, surely, was the purpose of treating the protesters in much the same manner as if they had been charged with armed robbery. The aggression displayed by police and prison guards was surely intentional, part punishment and part deterrent, even for individuals charged with minor crimes, and none of them yet tried or found guilty. Also disorientating was the absence of clocks, just as in casinos, and surely equally intended so that people lose track of time.

Before being allowed to use the phone, an officer needed to re-enter my details. I was called out of the holding cell, told to stand before a desk and spell my name. The officer could not hear me, so I explained it may have been my accent (I am British). For reasons that were unclear, the woman took offence. “Get back in the cell. You’ve lost your chance. You’re being condescending.”

I tried again to spell my name but they were having none of it. Out of nowhere, a male prison guard leapt at me from behind, yanked hard on the collar of my jacket, pulling it with sufficient force into my throat to make me gasp. He then manhandled me into the cell. I made a note of the man’s name, along with several officers who witnessed what he did.

A 53-year-old protester, Gina Hicks, saw what happened. “There was no attempt to have a conversation with you,” she later told me. “He just yanked you down and threw you back in the cell.”

‘Just keep your mask on and you’ll be fine’

Pasted on to the glass of every cell was information issued by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) on how best to avoid contracting coronavirus. It talked about social distancing, frequent washing of hands with soap, and wearing a mask.

The only option to wash my hands during the six or seven hours I spent in the jail was to use the drinking fountain, situated above the toilet, itself located behind a low brick wall that offered no privacy. The toilet was filthy, the room stank, one protester became ill and vomited in it. I requested some soap, and asked one of the officers what was the capacity for the cell.

What did I mean? Well, you know, you have signs about avoiding the coronavirus and yet there are 10 men in here, barely a foot apart. What is the capacity?

I had a similar conversation with a nurse from King County health department, an agency that has performed dogged work to counter the spread of coronavirus in Washington state, where the first case of Covid-19 in the US was reported in late January. The nurses were required to perform a basic medical on each of the people arrested.

She asked if I felt suicidal. Mental health is a major problem here, she said. I said I was most concerned about becoming dehydrated, having been told the only drinking water available was from that tap, from which I refused to drink, and getting infected with Covid. (She let me drink as many cups of water as I needed from the far more sanitary sink in the medical room.)

The fear of being infected is not paranoia. Eric Reinhart, a social anthropologist who teaches at Harvard, has studied how the constant arresting and processing of people for minor charges has acted to further spread the disease. Many jails, including Rikers Island in New York, and San Quentin in San Francisco, have been hotspots.

In 30 years as a journalist, this was the third time I had been detained. The first was in Cuba, the second in Pakistan, outside Bin Laden’s compound

Like many experts, he has called for the release of offenders charged with minor crimes, as a short-term fix.

Examining data from Chicago’s Cook County jail, which started testing new arrivals earlier this spring, Reinhart found one in six of all cases of Covid-19 in Chicago and the state of Illinois was linked to people jailed and released from this one establishment. He and a colleague, Daniel Chen, calculated that for each person cycled through the jail, an additional 2.1 infections were reported in that individual’s neighbourhood within a month. Around 60 per cent were in black-majority ZIP codes.

“This association between jail cycling and community spread of Covid-19 is particularly strong in communities of colour,” he told me.

Yet, Reinhart said, the focus on the overcrowded and unsanitary nature of prisons distracted from a broader truth about the racist underpinnings of the criminal justice system.

“There’s no other country that believes it’s necessary to arrest and incarcerate as many people as the US does. And it’s clear this does not produce more effective deterrence,” he said. He estimated the high arrest rate had added tens of thousands of Covid deaths to the total of more than 130,000.

He said there was “an exceptional historical opportunity to make clear to Americans who may have been resistant to recognising the problems in their criminal justice system”.

‘Take your hands out or I will punch you in the head’

After several hours, my feelings of bewilderment and anger were replaced by journalistic curiosity. Without intending to, Seattle’s law enforcement machine had provided with me with a rare insight into its workings. It was a brief, partial window into a criminal justice system seemingly bereft of humanity or equity: not for one second do I think what happened to me is comparable to the abuses enacted in this nation every moment on people without my white-skinned, press-badge privilege. Yet had I been allowed to remain in Cal Anderson Park and cover the police operation, I would not have seen or experienced what I did.

There was a tiny piece of pencil in the cell and I used it to make copious notes on scraps of paper. Among those in the cell was a young African American man called Kai. He had been at the protest site for 30 days and was arrested that morning. He said officers had kneeled on his back as they did so.

He also said he had been threatened by a female jail official, who told him to take his hands out of his trousers or she would “punch him in the head”.

When she came into our cell, another protester asked her if it was true she had threatened Kai. “That’s right, I did,” she replied. They asked for her badge number. A moment later she reappeared with a Post-It note, on which she had written her name and badge number with a smiley face. It felt like a flagrant display of swagger. Here, take my badge number. There’s nothing you can do to me.

Like everyone else, Kai had been charged with a minor offence, failure to disperse. Another man, Josh, 29, had not even been at the protest but was detained when he set off to get food from a local restaurant, and turned the wrong corner. 25%

of people incarcerated globally are in the US

He was charged with “pedestrian obstruction”. Another man, Daniel, who had been chanting “Black Lives Matter” in the prison van, was arrested in his car and charged with “vehicular obstruction”.

All were minor offences, so-called misdemeanours, for which bail was available, especially if you had no criminal history. The most serious charge I heard of that day was one handed to a man known as Trumpeter, whom I had seen at the protests a month earlier playing a guitar. He had been charged with “malicious mischief”, a more serious charge, for which he had been told he could not receive bail. Police claimed he had snipped through their “Do not cross” tape.

In 30 years as journalist, this was the third time I had been detained by the authorities. The first was in Cuba in 2006, while covering the announcement by Fidel Castro that he was standing aside. The second was in 2011 in Pakistan, while taking photographs outside Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, six months after he had been killed by US Special Forces.

My encounter with Seattle police was the first time I had been arrested. I had no criminal record. As a result, I was released at 6pm after signing a piece of paper saying I would show up for court.

Among the 30-odd people discharged with me that evening was a young African American man who said he had spent an entire year in jail after being charged with resisting arrest. He said he had been unable to make bail. He was far from alone. Campaigners say hundreds of thousands of people, not actually convicted of a crime, are sitting in America’s jails because they do not have the means to pay a bond agency.

Journalism is not a crime

Seattle’s Cal Anderson Park was established 100 years ago but given its current name in 2003 to honour Washington state’s first openly gay legislator, who died from Aids in 1995. In the years since, it has become a place for both protests and celebrations, along with simply sitting in the sun enjoying a picnic. Most years, July 4th will see it packed with people watching fireworks.

On Saturday, my wrists still sore from the handcuffs and my throat tender after having the jacket tugged down hard on it, I donned a face mask and cycled around the park’s perimeter, shut off with tape. At each entrance was a small group of police officers. At the East Precinct building, workmen were repairing damage caused during the protests. A few Black Lives Matter logos appeared from various shop windows, but the protesters were gone, a small number that day marching outside the West Precinct.

The night before I’d watched Donald Trump deliver what was widely perceived as a divisive speech against the backdrop of Mount Rushmore, where among other things he accused the media of promoting a “new far-left fascism that demands absolute allegiance”.

Trump vowed to honour the “heroes” carved in stone, which he used for his backdrop. Among them were presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, two founding fathers of the nation, who were also slave owners. Indigenous protesters said the land was theirs and demanded Trump call off the event.

On Saturday, the president reinforced his sentiments at the White House. “And we will defend, protect and preserve the American way of life, which began in 1492 when Columbus discovered America,” he said.

This time, he was met with more protesters, some pointing to the organised killing of countless thousands of indigenous people that was also central to the nation’s development. According to reports some chanted: “Slavery, genocide and war – America was never great.” In Baltimore, a statue of Columbus was pulled down and thrown into the harbour.

On my circuit around the park, I intentionally did not stop to speak to anybody. Since being released from jail, I have become increasingly sick. Headaches, a cough, exhaustion. On Monday I got a Covid test. Two days later, I was relieved when it came back negative.

I am also expecting a letter from the court, with a time and date to attend; while the mayor said last week she hoped prosecutors would drop the charges against the protesters, I have received no such message.

The SPD said it had forwarded details of my arrest to the Office of Police Accountability for review, and King County sheriff’s department said it was looking into my assertion I was assaulted by one of its officers, that a female officer threatened a protester, and that its facilities to address coronavirus were inadequate. It said it had been SPD officers who had taken me to the jail in a “belly chain”. The SPD did not not immediately respond to questions about this.

Asked to comment on my interaction with FBI officers, bureau spokesperson Steve Bernd said: “I would not be able to speculate or provide a comment regarding the incident you describe below and would refer you to the Seattle Police Department.”

The park has a reflecting pool, where people sit and read, or think or listen to music. It was also off-limits, but I did not need to spend time there to be certain that if I am charged, I will be pleading not guilty. Journalism is not a crime.

At the same time I will be trying to explain why, supported by the right afforded by the First Amendment of the Constitution, I stood my ground.

In Trump’s America, where the media is routinely cast as evil and dishonest and where an African American reporter for CNN can be arrested live on air, the need to defend journalism and its centrality to an informed democracy has never been greater. And the foundational act for journalists is to show up, either literally or else in spirt and commitment and focus.

Whether we’re covering the actions of a city council, the workings of Wall Street, or the faltering, long-overdue attempt of a nation to confront the racial inequities that underpin its creation, the most important thing is to pledge ourselves to the task of doing so, and then get on with it.

Our job is not to disperse. Our job is to be present.