The summer of 2020 was not the first time America saw protests and violence over the treatment of African Americans.

Long before the demonstrations over Black Lives Matter, long before the marches of the Civil Rights era, strife over racism convulsed the nation’s capital. But those riots in Washington, D.C to protest the escape of the Black slaves were led by pro-slavery mobs.

In the spring of 1848, conspirators orchestrated one of the largest escapes from slavery in U.S. history. In doing so, they sparked a crisis that entangled advocates for slavery’s abolition, white supremacists, the press and even the president.

Daniel Bell, a free Black man in Washington, wanted to liberate his enslaved wife, children and grandchildren. Citing a promise of freedom from their onetime owner, he tried but failed to do so through the courts. So he started planning an escape. A lawyer he consulted knew of others eager to flee lives of bondage. He and Bell decided to help them all.

They approached Daniel Drayton. A sea captain, he had carried small groups of fugitives to freedom. For $100, he agreed to hire a ship for this larger scheme. Drayton, in turn, paid $100 to fellow captain Edward Sayres to charter his schooner, the Pearl.

On the night of April 15, the Pearl left Washington. Seventy-six Black men, women and children, having quietly left area farms, hid beneath the deck. Drayton and Sayres steered the ship down the Potomac River. They were bound for Philadelphia, where slavery was illegal.

The fugitives did not get far. Owners soon noticed their absence and formed a posse to find them. The posse, aboard a steamboat, overtook and commandeered the Pearl as it entered Chesapeake Bay on April 17. The next day, the fugitives and their white abettors were marched through Washington and thrown in the city jail.

Riots in the capital

Furious at the conspirators’ challenge to the social order, Washington’s white population wanted to punish someone. With Drayton and Sayres awaiting trial behind bars, white supremacists turned against the abolitionist press.

Opponents of slavery published several newspapers promoting their cause. In Washington, Gamaliel Bailey Jr. had founded the National Era in 1847. Bailey and his paper opposed escape attempts but supported ending the slave trade and eventually slavery itself.

The nights of April 18 and 19, thousands gathered outside the National Era’s offices. They gave speeches and spread a false rumor about journalists’ involvement in the Pearl escape. The protesters’ leaders reportedly included U.S. government clerks.

Soon the protesters turned violent. They threw rocks at the building the first night and intended to destroy it the second. Both nights, though, they dispersed when confronted by local police.

Presidential intervention

The crisis had begun with slavery. Of the more than 3 million Black Americans in 1848, nearly 90% were held in bondage. They lived and worked on Southern farms owned by the same white men who claimed them as property. Each year, thousands of them fled in search of freedom.

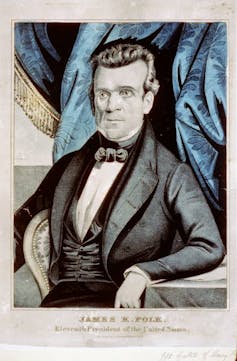

James K. Polk, the nation’s president, both defended slavery and enriched himself by it. He owned more than 50 workers on his Mississippi cotton plantation. While editing his letters, the final volume of them just published, I often read his complaints about escapes from there. Like other slave owners, he relied on relatives and paid agents to capture, return and physically punish the fugitives.

After the Pearl escape, Polk shared the rioters’ belief in white supremacy and their indignation at resistance to enslavement. He also shared their hostility toward abolitionists and pro-reform newspapers, blaming those in his diary for the whole incident: “The outrage committed by stealing or seducing the slaves … had produced the excitement & the threatened violence on the abolition press.”

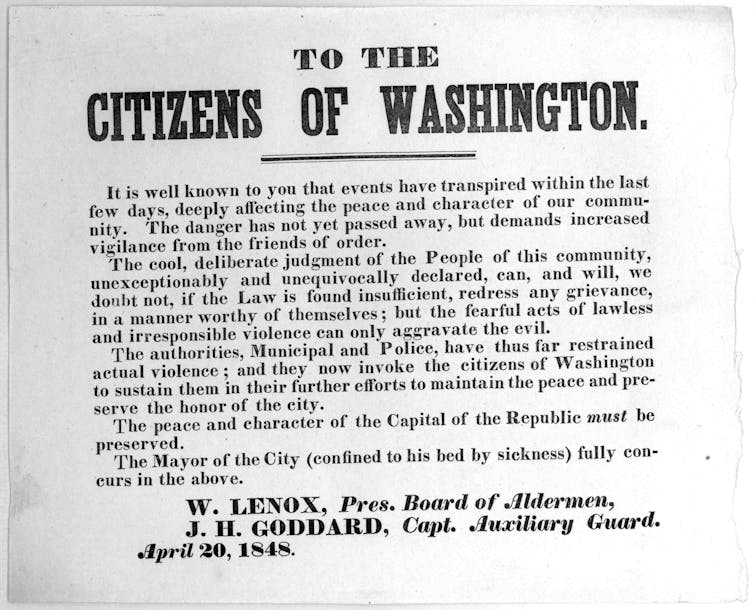

Yet, by April 20, the president was worried about the violence in Washington. Federal employees’ involvement especially troubled him. He ordered them to “abstain from participation in all scenes of riot or violence” and threatened those who disobeyed with prosecution.

Polk also directed the U.S. deputy marshal, Thomas Woodward, to cooperate with local law enforcement in suppressing the riots. As Polk told an adviser, he intended to “exercise every constitutional power … with which the President was cloathe’d” to restore peace.

It worked. When the mob reassembled at the National Era the night of the 20th, it was successfully countered by city and federal officers. About 200 rioters moved on to Bailey’s home, threatening to tar and feather him. But he managed to talk them down, even earning applause for his speech from the formerly hostile crowd.

The violence was over.

Losers and winners

Captains Drayton and Sayres suffered for their efforts. Convicted of illegally transporting slaves, they remained incarcerated until President Millard Fillmore pardoned them in 1852.

Even worse off were the people they had helped escape. Abolitionists bought a very few their liberty, but nearly all returned to slavery. Many were sold farther south, more distant than ever from their dream of freedom.

The National Era, aside from broken windows, emerged unscathed. City and federal authorities, by ending the riots, had protected the press’s freedom to print unpopular views. The rioters, too, came out just fine. Not one was charged with a crime.

Polk, perhaps, benefited the most. He avoided major bloodshed on his watch and earned praise for cooperating with local police.

Yet he never questioned the rioters’ complaints or the racist society they defended.