- The Western sanctions on Russia were predicted to inflict unbearable pain on Putin’s government. The EU’s dependence on Russian energy has prevented that from happening so far, and Russia’s export outlook continues to look good in the near term

Since February 23, the day before Russia invaded Ukraine, the European Union’s Council has adopted six rounds of sanctions to “impose clear economic and political costs” on the government of President Vladimir Putin, and to “cripple the Kremlin’s ability to finance the war”.

Western governments, including the United States and United Kingdom, have cut off major Russian banks from SWIFT, the interbank messaging system to enable cross-border payments. They have frozen some $315 billion out the $550 billion of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation’s (CBR) foreign exchange reserves held in currencies and gold within their jurisdictions, as on January 1.

On April 6, the White House issued a statement that the “most impactful, coordinated and wide-ranging economic restrictions in history” would cause Russia’s GDP to “contract up to 15 per cent this year, wiping out the last 15 years of economic gains”.

Has the West’s intent been borne out by reality?

More than four months into the war, the story hasn’t quite followed the West’s predicted script. To begin with, the latest median forecast of GDP decline for 2022 — based on a survey of 27 economists from various organisations (including the likes of Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs and J P Morgan) conducted by the CBR between May 25 and 31 — is at 7.5%. This is better than the –9.2% average growth forecast made in a previous survey from April 13-19.

The median forecast of consumer price inflation for the year too, has fallen from 22% to 17% between the two surveys. Also read |Biden: G-7 to ban Russian gold in response to Ukraine war

The sanctions initially led to a free fall of the Russian ruble, from about 76 to the US dollar in mid-February to a low of 158.3 on March 7. The CBR was forced to raise its key interest rate from 9.5% to 20% on February 28, which was aimed as much at bolstering the currency — which US President Joe Biden had mocked as “rubble” — as at reining in inflation risks.

But as the ruble bounced back to 75-76 levels towards the second week of April — and is currently trading at over seven-year-high levels of 53.4 to the dollar. And the central bank slashed its key rate to 17% on April 8, to 14% on April 29, 11% on May 26, and to 9.5% on June 10.

With the ruble appreciating, inflation trending downwards (rather than upwards, as predicted by the White House) and GDP unlikely to shrink quite as much as predicted, the West’s sanctions have not had their intended effect.

Nor has Russia’s external trade really suffered. The country’s surplus of goods and services exports over imports has widened, from $44.5 billion in January-May 2021 to $124.3 billion in January-May 2022. So has its overall current account surplus — from $32.1 billion to $110.3 billion — for the comparable periods.

Why do the sanctions appear not to have had the desired effect?

The main reason is the dependence, especially of EU countries, on energy imports from Russia. In 2021, Russia accounted for 25.7% of the petroleum oil, 44.5% of natural gas, and 52.3% of the coal imported by the 27-nation bloc.

During the first 100 days of the war, from February 24 to June 3, Russia’s revenues from fossil fuel exports totalled 93 billion euros ($98 billion), according to the Finland-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

That included 46 billion euros from crude oil, 13 billion euros from refined oil products, 24 billion euros from pipeline gas, 5.1 billion euros from liquefied natural gas, and 4.8 billion euros from coal. Out of the 93 billion euros, the EU’s share alone was 57 billion euros or 61%.

In its sixth “package” of sanctions on June 3, the EU decided to phase out imports of crude oil and refined products from Russia over six and eight months respectively. Temporary exemption was granted to countries such as Hungary and Slovakia, which import crude oil by pipeline and “have no viable alternative options”.

This was preceded by an outright prohibition on Russian coal imports from August, as part of a fifth round of sanctions on April 8.

It remains to be seen how successful these import phase-out plans will be, in terms of implementation on the ground. The test will be in the winter, when energy demand peaks.

Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, recently warned that Europe is at risk of energy rationing, particularly “if we have a harsh and long winter”, and if the cold weather coincides with resurgent demand in China post the lifting of Covid lockdowns there.

The EU for now has not announced any ban on natural gas imports from Russia. This, even as the Russian state-owned energy giant Gazprom has cut gas supplies to nearly a dozen EU countries, including Germany, France and Italy, over the past few weeks.

Have China and India had a role to play in this situation?

It is significant that China and India have emerged as major buyers of Russian fossil fuels. CREA’s latest tracker shows Russia’s cumulative exports of oil, gas, and coal to the EU since February 24 at around 64.4 billion euros.

But among individual countries, China (16.6 billion euros) has surpassed Germany as the largest importer from Russia. At No. 8 is India. Its imports during this period are valued at 3.7 billion euros, comprising 3.2 billion euros of oil, and the balance coal.

While the EU is trying hard to wean itself off Russian energy, Moscow has aggressively diversified its exports towards China and India. China was the world’s top importer of crude oil in 2021, with India ranked third behind the US.

In May, Russia overtook Saudi Arabia to be China’s leading crude supplier. In 2021-22, Russia was the ninth biggest crude exporter to India. However, by May, it had jumped seven positions to displace Saudi Arabia and become No. 2 after only Iraq.

By continuing to sell to the EU, and at the same time ramping up exports to China and India by offering steep discounts on international prices, Russia has effectively blunted Western sanctions.

Does this mean sanctions targeting Russia have ended up hurting the West?

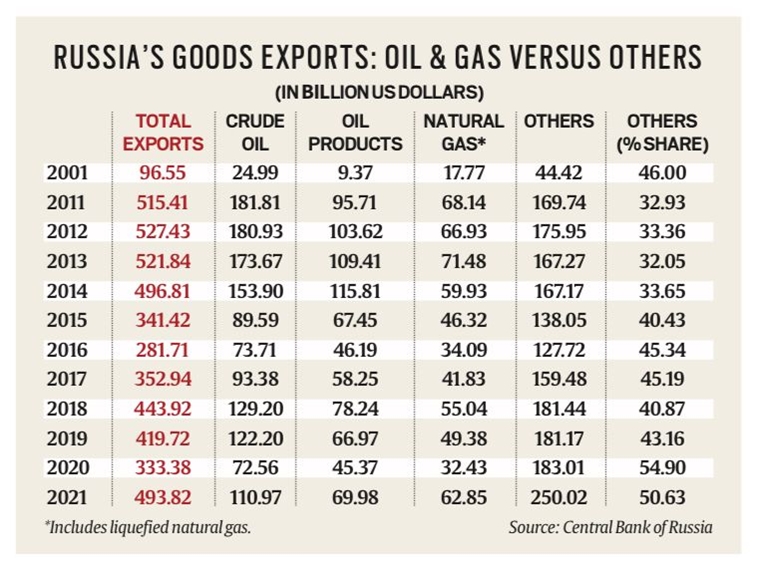

The table shows the share of oil and gas in Russia’s merchandise exports at close to 50% in 2021. It was 66% during 2011-14, when crude prices averaged over $100 per barrel. High prices are again benefitting Russia, although its average oil production has fallen to 10-10.1 million barrels per day (mbd) in April-May, from 11-11.1 mbd in February-March. The table shows the share of oil and gas in Russia’s merchandise exports at close to 50% in 2021.

The table shows the share of oil and gas in Russia’s merchandise exports at close to 50% in 2021.

As Russia has increased efforts to find alternative markets and the world is figuring out ways to trade with it, the country’s exports may not drastically drop from the $494 billion of 2021.

Again, it isn’t just fossil fuels. In the coming months, one can expect Russia to step up exports of wheat and fertilisers. Being also the world’s biggest supplier of palladium and nickel — which are central inputs in emission control systems and electric vehicle batteries respectively — besides ferro-alloys, chromium and vanadium (required for steel production), makes it easier for Russia to cope with sanctions than it is for Cuba, Iran, or North Korea.

Europe and the West might be discovering that sanctions are perhaps hurting them more than they are hurting Russia.

First published in Indian Express, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/russia-ukraine-european-union-why-sanctions-are-flagging-7992798/?utm_source=newzmate&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=morningbrief&pnespid=ArsjqUJe6XkMiV_S7sHTFUZO_Bsn0rUr_l9eQ6YTNIDKGG.96mqyHu2F_kjdbMPnuNhjV5iK