By Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo

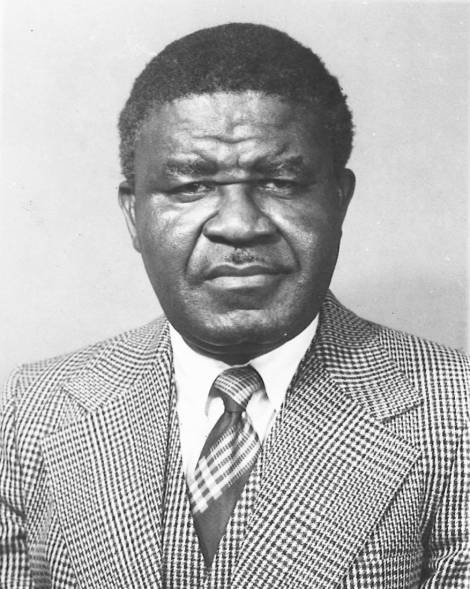

I did not study history in senior secondary school. Yet, if I know history better than most, it is because I stand on the shoulders of a giant: Professor Chieka Ifemesia.

While many young Nigerians today attend secondary schools devoid of history classes, my era still included the subject in the curriculum. I longed to study history, just as my father had. However, as a science student, I had to choose between history and literature. I chose literature, leaving me to pursue history on my own. It wasn’t a simple path. Without a solid foundation, gaps in my knowledge remained—until I met Professor Ifemesia.

In 2004, I lived a stone’s throw from Professor Chieka Ifemesia in Bay Shore, New York. People who studied history in Nigeria must have encountered him along their academic path. I didn’t. The credential I used to pass through the door was that I married the daughter of his beloved Ogidi.

That was how I started partaking in my private moonlight tales in his house. Most evenings after the day’s work, I would slide over to his house and have him tell me stories about Nigeria that only a few people knew. Sometimes, his children sat in and listened. But most times, it was our special moments.

Professor Ifemesia wasn’t just a historian by training; he was a historian by essence. He embodied history, having lived through pivotal moments in Nigeria’s past.

In 2004, he was already about eighty and retired. Born in 1925, he lived through the colonial era and watched them come, intervene in our affairs, and return to their cold homeland. In our conversations, he clarified what his unique generation that witnessed colonization up close learned.

His understanding of the Europeans and their adventures in Africa was profound and nuanced. The central thesis of the historical pronouncements in his published books was how the Europeans damaged our society within one lifetime. “Two ideas of nation-building have been in conflict in Nigeria since amalgamation,” he argued consistently in his numerous lectures and public interventions.

Like every historian of remarkable insight, the urgency of his thoughts and musings was on how to remediate the damage while we still had men and women like him who knew where the proverbial water entered the husk of the melon. His voice always carried an imperative tone when enumerating what was at stake. An air of exigency engulfed the living room of his home whenever he was in that zone. Observing his insistence in detailing the solutions, I often wondered if what I witnessed was not a transfer of a message from our ancestors to our generation.

Ifemesia’s generation fervently fought for Nigeria’s independence. His participation had the extra oomph because of his understanding of the “things that fell apart” because of the European incursion. Like men and women of his generation, he was optimistic about the heights his generation would take Nigeria to.

During the brief administration of General Aguiyi-Ironsi as Head of State of Nigeria, Ifemesia, then a lecturer at the University of Ibadan, was appointed a member of an inquiry in Lagos looking at the issues at the Nigerian railway. Days after the countercoup that killed Ironsi, he returned to Ibadan from Lagos. At his house, he encountered an army officer and two constables armed with a search warrant seeking arms and ammunition. He only granted them entry after searching them himself, emptying their pockets to ensure they didn’t have incriminating items to plant inside his house. That same night, he left Ibadan for the Southeast, aware that the rest of Nigeria was no longer conducive for the Igbo.

When the dreams of Nigeria crumbled, Ifemesia was there as both a witness and a participant.

During the Biafran war, he was one of the intellectuals around the Biafran leader, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu. He was to Ojukwu what Karl Rove was to President George W Bush or what David Axelrod was to President Barrack Obama, a senior policy adviser and strategist. His personal account of what transpired during the war was as important as those of combatants on the war front. His front-row seat gave him a unique view of history that we often miss in narratives of world events. He told me that when the Biafran war was ending and Ojukwu was about to leave for exile, he was one of those penciled down to go with Ojukwu. But he decided against it, choosing to stay with his family, despite the risk.

Spending time with Professor Ifemesia was akin to earning a degree in history. I once asked him what he and his colleagues at the National Guidance Committee of Biafra, which included Chinua Achebe, had in mind when they penned the famous Ahiara Declaration. His answer was quintessentially academic: they sought to leave a document of purpose—a guide for future generations. He even urged me to cross-check his account with Achebe himself, which I did.

I took journalists and researchers to his house several times to interview him. International journalist Chika Oduah had such an interview for her Biafra Memories project. I also accompanied Professor Obiora Udechukwu to Ifemesia’s house for another learning session from his deep knowledge tank.

Ifemesia’s passion for the Igbo people was unmatched. One of his most striking reflections, which I often quote, was, “Things others did to us were many, but things we did to ourselves were more.”

He lived with the clarity of someone aware of his role in history and his duty to posterity. As a teacher, he embodied the ideals he preached, often citing Muhammad Ali’s adage: “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth.”

Professor Ifemesia’s journey was extraordinary. Following his father’s death at seven, his uncle raised him and sent him to missionary schools in Ogidi, Bukuru, and Jos. From Dennis Memorial Grammar School in Onitsha, he advanced to University College, Ibadan, and later King’s College in London. He returned to Nigeria to teach at the University of Ibadan and later the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN). His career took him to the University of California and various institutions in New York, including Medgar Evers College and Adelphi University.

From all accounts, his students loved him and enjoyed his broad knowledge of colonial and post-colonial African history. While teaching in America, he piqued his students’ interest in the affairs of Africa, the often forgotten continent. He challenged them to question dominant conventional wisdom about Africa as the Dark Continent in need of civilization. He did so without compromising the rigorous high standards he grew up with in Nigeria. Those he mentored attest to his generosity. Those lucky enough to benefit from his vast knowledge will always remember his exceptional teaching abilities.

I felt richer each time I left Ifemesia’s house after long hours of listening to his enchanting narration of our history, which he did with the zeal that mirrored that of ancient bards weaving folktales. Looking up as I step outside his house, his wisdom and knowledge multiply the stars in the sky.

Professor Ifemesia has joined our ancestors at 99. He is now part of the stars in the sky, and I feel his presence each time I look up at the night sky.

Ugodiadi na Ikenga Ogidi, ka emesia. Ka chifo, Onye Nkuzim, Prof. Ifemesia.

Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo teaches Post-Colonial African History, Afrodiasporic Literature, and African Folktales at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He is also the host of Dr. Damages Show. His books include “This American Life Sef” and “Children of a Retired God.” among others. His upcoming book is called “Why I’m Disappointed in Jesus.”