Jason Burke, Africa Correspondent, The Guardian

- A new generation could end decades of MPLA rule this week and serve notice on Africa’s veteran leaders in polls seen as test of democracy

Millions of Angolans will vote this week in a landmark election described as an “existential moment” for the key oil-rich central African state, and a test for democracy across a swath of the continent.

The poll on Wednesday pits veteran politicians against a generation of young voters just beginning to grasp that they can bring about a radical change and escape from the shadow of the cold war.

Observers say discontent with the rule of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), in power since Angola declared independence from Portugal in 1975, has reached a point where the party will only now secure another five years in power through rigging and repression.

“It is an existential election, and it is going to be very tight race. If there were free and fair elections, there is no doubt the opposition would win but the government is not going to allow that,” said Paula Cristina Roque, an independent analyst and author.

Other parties and leaders that have remained in power for decades since winning liberation struggles on the continent are likely to see the growing difficulties of their counterparts in Angola as a warning.

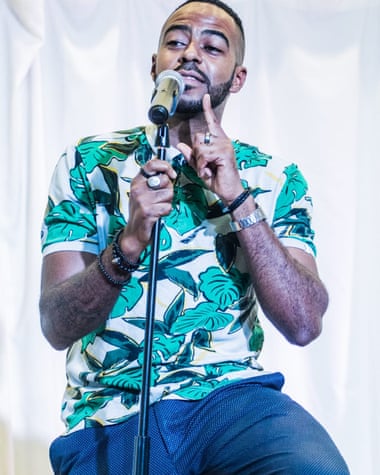

Tiago Costa, one of Angola’s new wave of comedians, said young voters need to step up and make the country a better place. Photograph: GOZ’AQUi

As elsewhere in Africa, a key factor in Angola is the youth of the population. More than 60% are under 24. Tiago Costa, one of the most successful of a new wave of comedians and other creative artists in Angola, said that the millions of young people voting for the first time had values and views that are dramatically different from those of their politicians.

“We are just living the same thing over and over again. Young people in Angola are asking: ‘What is going on here?’ These kids are lost in these speeches and stories that they just don’t understand or deserve,” said Costa, 37.

“Young people here need to learn from the mistakes of their elders [and] step up to make Angola a country for Angolans, not for parties that are always dividing us and never doing their jobs.”

President João Lourenço, a veteran MPLA official and former defence minister, won power in 2017 as the handpicked successor to José Eduardo dos Santos, whose authoritarian rule lasted 38 years.Advertisementhttps://af95a034acea7c46cd0b607e147974c5.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

Though Lourenço, 68, has tried to boost economic growth and pay off vast debts, he has failed to improve the lives of most of the 35 million population. Critics say a high-profile anti-corruption drive only targeted potentially powerful enemies – such as Isabel dos Santos, the hugely wealthy daughter of the former president – while Amnesty International has described “an unprecedented crackdown on human rights, including unlawful killings and arbitrary arrests, in the lead up to the 24 August election”.

Analysts said that, when presented with a choice between saving the MPLA or saving the nation, Lourenço put the party first. “They were not going to reform themselves out of power,” said Roque. “For a long time Angolans said: ‘We are poor, we are struggling, but we are at peace and that’s enough.’ But now they are angry and disappointed and have nothing to lose.”

A boom that followed the end of the brutal 27-year civil war in 2002 largely benefited the elite. Life expectancy in Angola remains one of the lowest in the world, services are patchy and millions live in misery despite the country’s massive earnings from oil exports.

“Most people I talk to say that Lourenço has done nothing for them during these five years,” said Laura Macedo, an activist who campaigns for better conditions for those in Luanda’s sprawling poor neighbourhoods. “Most are planning to vote for the opposition”.Advertisement

Lourenço’s principal rival is Adalberto Costa Júnior of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (Unita). Though only eight years younger than the incumbent, Costa Júnior has tried to position himself as a representative of the young civil society and all those who have lost out under the years of MPLA rule.

Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of former president José Eduardo dos Santos, built a huge fortune, but was the target of a high-profile anti-corruption drive. Photograph: Bloomberg/Getty Images

Unita was once the proxy of the west, funded and armed by the US and its allies, but eventually losing the civil war to the MPLA, which was backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba.

Under Costa Júnior, the party has shifted to the centre but is still seen as pro-western and pro-business, contrasting with the MPLA’s socialist ideological background and continuing links with Russia.

Angola, with its massive oil reserves, is now a key zone of great power competition once again. Beijing has lost ground in recent years after José Eduardo dos Santos racked up massive debts to China to pay for what have often been shoddily constructed or badly designed infrastructure projects. Both Russia and the US have made efforts to win influence in Luanda too.

The conflict in Ukraine has intensified rivalries across the continent. Angola was among 17 African countries that refused to support a UN general assembly motion condemning the Russian invasion, leading some to describe a “new cold war” on the continent.

Both Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, and Antony Blinken, the US secretary of state, have toured Africa in recent months in an effort to reinforce relations on the continent. Neither stopped in Luanda, though both paid attention to central Africa.

Unita officials say they are prepared to wait another five years before taking power, but the difficulties of the MPLA underline the challenges faced by many other parties or leaders that came to power in the aftermath of conflict on the continent.

You can rig elections but it doesn’t get rid of the anger. The risk is the frustration comes out in riots … and unrest

Nic Cheeseman, professor of democracy

In Uganda, 77-year-old Yoweri Museveni has ruled since 1986 and is facing a powerful opposition movement led by former musician Bobi Wine that has won support among the young and city-dwellers. A recent poll put Nelson Chamisa, leader of the opposition in Zimbabwe, three points ahead of the Zanu-PF party, which came to power in 1980.

The ANC in South Africa was led into government by Nelson Mandela after the fall of the racist apartheid regime in 1994 but has also suffered a steep loss of support. Recent surveys suggested the party could drop to 38% in elections in 2024, potentially ending its rule or forcing a new era of coalition politics in Africa’s most industrialised country.

Nic Cheeseman, professor of democracy at Birmingham University, who specialises in African politics, said existing problems had combined with the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the continent and recent global increases in food and fuel prices to prompt a wave of discontent that threatened to destabilise governments everywhere – authoritarian and democratic.

“You can rig elections and keep power but it doesn’t get rid of the anger. The risk then is that the frustration comes out in other ways, with riots, political violence and unrest,” said Cheeseman.

This may be a risk that the west – avid for new energy supplies – will be prepared to take.

“Angola has oil. The west needs energy security. So even if the MPLA keeps power through fraudulent elections, the west will continue to put stability before democracy,” said Roque.

First published in The Guardian (UK)