As cases of out-of-school children in Nigeria increase by the day, stakeholders have expressed concern that the nation is at a great risk of losing out on a literate and skilled workforce it needs to grow economically.

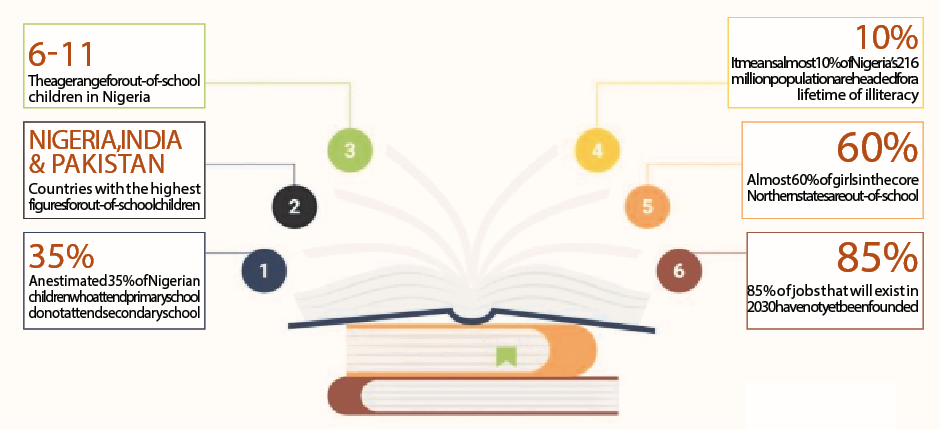

According to the United Nations, out-of-school children refer to children who are yet to be enrolled in any formal education, excluding pre-primary education. The age range for out-of-school children is 6-11 years.

Data compiled by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), in partnership with the Global Education and Monitoring Report, showed that Nigeria has about 20 million out-of-school children, placing it second after India, a nation with over one billion population. Pakistan comes third. The three countries have the highest figures for out-of-school children globally.

Findings by LEADERSHIP Data Mining Department revealed that the situation had been growing worse due to the degenerating security situation in the country. Ten states are at the top of the log regarding Nigeria’s 20 million out-of-school children. Kano State leads the pack while Akwa Ibom, Katsina and Kaduna follow closely. Other states that rank high on the list are Taraba, Sokoto, Yobe, Zamfara and Bauchi. Cross River, Abia, Kwara, Enugu, Bayelsa, Ekiti and FCT are states with the lowest numbers of out-of-school children.

Findings also showed that 26 of 36 states failed to provide the matching funds needed to access the N33.6 billion funding provided for rehabilitating basic schools by the federal government through the Universal Basic Education Fund between 2015 and 2021. ADVERTISEMENT

Experts said rising insecurity across the country, causing mass displacement; poor funding; rising poverty that forces parents to put children in the labour market and street hawking, and the breakdown in social and family life are some of the causes.

An education advocate, Mariam Zakari, said some states have failed to domesticate the Child Rights Act 2003. Over the years, successive governments have adopted programmes to foster free, compulsory child education, culminating in the National Policy on Education 2004 and passage of the Child Rights Act 2003 which mandates nine years of compulsory schooling for children.

She said, ‘‘Some states have failed to domesticate the Child Rights Act 2003, most of them are in the North, the region that hosts the largest number of out-of-school children. Nigeria domesticated the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of a child by passing the Child’s Right Act (CRA), but the law is not enforced.

The director of Programmes, Education For All Foundation, Emeka Uwajare, said Nigeria is where it is because of poor investment in the education sector.

He lamented that the nation’s funding for education remains less than 10 per cent of the yearly budget, far from the 15 to 20 per cent recommended by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO).

He, however, pointed out that with many children kept out of school, Nigeria cannot adequately compete in a knowledge-based economy globally.

A World Bank document entitled “Nigeria Development Update (June 2022): The Continuing Urgency of Business Unusual,” revealed that with many children out of school in Nigeria, in years to come, there will be a lack of adequate and appropriate manpower in the future.

Also, a study showed that children who are out of school are often used to perpetrate crime and other ills in the society. Corroborating this view, a human resources expert, Dele Oke, said this deficiency will affect all aspects of human life as there will be vacancies in several areas that demand skills acquired through education at school.

According to an educationist, Rukayat Garba, the 20 million out-of-school children represents a grim future, one characterised by grave socio-economic and security consequences for Nigeria.

She also said that with the slow economic but high population growth in Nigeria, particularly in the North, regardless of what others may say, it is in the interest of the government to educate its youth on different skills that create jobs as a formidable way of curbing crime and reducing insecurity.

According to her, with Nigeria’s population of 216 million means, almost 10 per cent of its people are headed for a lifetime of illiteracy. For a country with a literacy rate of just 62.02 per cent, she said all efforts should be geared towards achieving mass literacy, not nurturing another generation of illiterates.

An educationist, Dr Zikirullahi Ibrahim, stressed the need to re-strategise and refocus towards addressing the issue of out-of-school children in Nigeria.

Speaking exclusively in an interview with LEADERSHIP Friday, the executive director, Centre for Human Rights and Cvic Education (CHRICED) said it is posing a serious threat to the future of the country.

He said, “We all know what it means to breed children who lack education and skills to compete in the current market economy that we are running globally. It appears that at the very early stage of our development in this country as a nation, education was taken into consideration in such a way that they were able to factor it in, knowing that there are some who do not have. If they are left behind, those children that we are not able to train will pose danger to those that have and were able to train their children.

“That was why they came up with the policy of Universal Basic Education (UBE) – which mandates the government at the state and federal levels to give compulsory, free and quality education to every child of school age. Now the question is what has happened to this policy? How has it been implemented so far? So, we have seen UBEC and most officials that pass through UBEC are far richer than education ministries in various states. We have seen those managing state universal basic education far richer than their ministry. So, it has become a big business, just like corruption has crippled every other sector of our development.

“Today, you’ll find about 500 school pupils clustered in one classroom, sitting on the floor, so unhygienic – no basic water, no electricity, no ventilation, no security – so they are exposed to all kinds of elements. There is also a correlation between out-of-school children and insecurity we have in our system today, and when you put it in a proper perspective, you say that in developed nation, it’s not because they don’t want to do it but because they know the importance of not leaving anyone behind; that is the reason, we should use social security system. We need to re-strategise, we need to refocus, we need to go back to the drawing board to really address these issues of out-of-school children.’’

Another educationist, a quality assurance officer in Benue, Moji Francis, said the spate of attacks on schools and abductions of students in the country have also contributed to the increase in the scourge of children not going to school.

She said, “Currently, in Nigeria, there are over 20 million out-of-school children, 60 percent of whom are girls. That is over 10 million girls are out of school and the majority of these out-of-school children are actually from Northern Nigeria. This situation will create a serious effect in all the activities of the country, from the economy to literacy, hence the need for all hands to be on deck to eradicate this.”

A parent who resides in Mararaba, Nasarawa State, Mrs Gloria Isaac said the Nigerian girl-child is seriously endangered and under threat given the rate of girls who are out of school.

“When girls are denied education, you are denying roughly half of the nation’s population from being emancipated and preventing progress,” she said.

A 2022 report on the UNICEF website paints a grimmer picture. It says an estimated 35% of Nigerian children who attend primary school do not attend secondary school. In many instances recently, children who go to school get abducted by terrorists.

LEADERSHIP Data Mining department’s findings showed that the Northern part of the country has very troubling school attendance rates, with states like Borno, Bauchi, Sokoto, Gombe, and others with out-of-school rates that hover between 48-60% and early education enrollment rates that are only between 3% and 7%.

The out-of-school figures for female children in the core Northern regions are very troubling because they show that almost 60% of girls in those areas are being deprived of the education that would equip them with the tools required for optimal socioeconomic performance.

Future of work

Simply put, the future of work is a projection of how work, workers and the workplace will evolve in the years ahead. A 2020 research report from the Society for Human Resource Management and Willis Towers Watson noted that “85 percent of jobs that will exist in 2030 have not been invented yet.”

According to an employer, Malik Mohammed, while much focus is placed on technology in future-of-work discussions, other factors, such as remote employment and the gig economy, play a large role in not only how work will be done, but who will be doing it and from where.

He said, ‘‘From all indications the future of work is solely reliant on technology. The big question is, does Nigeria have the skilled manpower and capacity to handle the big transformation, especially in the public space?’’

First published in Leadership